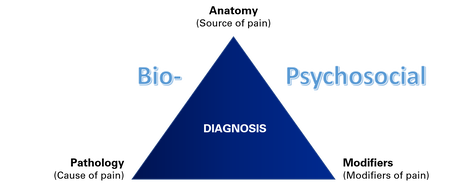

The debate between "diagnosis" vs "no diagnosis", and the "pathoanatomic diagnosis" vs "psychosocial" approaches to the assessment and management of pain is prominent in social media circles. Sides are chosen, battle lines are drawn and shots are fired in a battle that is fought between colleagues from within- and between professions. Many enter the battle without fully understanding the concepts of diagnosis, central sensitisation and psychosocial modifiers and how they are all related. Some steadfastly defend their position for other reasons. Like anything in healthcare, nothing is ever black and white, and if we choose a side and take up arms against the perceived enemy, the biggest casualty ends up being our patients. Flavio Bonnet from the Agence EBP provided the forum for a discussion on this topic between myself and Dr Mark Laslett. In a live social media event, we discussed the relationship between patho-anatomic diagnosis and psychosocial factors in our respective areas of low back pain (Mark) and shoulder pain (myself). The discussion streamed live on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram from Christchurch, New Zealand on 18th March 2019 with the event viewed by more than 7,500 people from around the world. In this series, I provide a summary of the main points from the key topics in our discussion: 1. Is it possible to make a diagnosis? 2. Does the pathoanatomic approach ignore the psychosocial aspect of the pain experience? 3. What do you say to colleagues who say that diagnosis does not change treatment? 4. How does imaging relate to diagnosis? You can also watch a video recording of the full discussion by clicking on the link below. Link to video on Twitter: https://twitter.com/marklaslett_NZ/status/1107733389300240384 PART 1. Is it possible to make a diagnosis?

A summary of discussion points on this topic is provided below. To download a more detailed transcript on this topic, click on the file link below. SUMMARY:

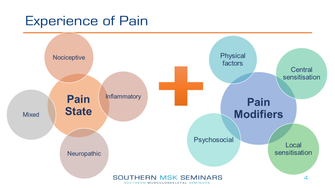

PART 2: Does the pathoanatomic approach ignore the psychosocial aspect of the pain experience?

In Part 2 we discuss the relationship between pathoanatomy, central sensitisation and psychosocial factors, and look specifically at:

SUMMARY:

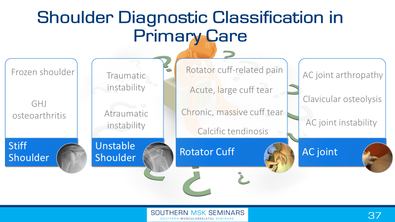

PART 3: Does diagnosis change treatment?

In Part 3 we discuss whether we need a diagnosis in order to treat a patient effectively and, if so, what types of diagnoses are helpful in guiding management? SUMMARY:

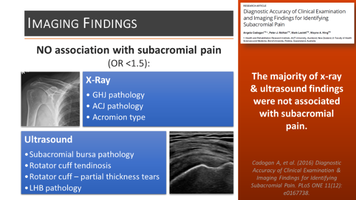

PART 4: How does imaging relate to diagnosis?

In Part 4 we discuss where imaging fits in the diagnostic process, who should we be imaging and how to interpret the results in the context of a high prevalence of findings in asymptomatic populations.  SUMMARY:

Questions from Social Media:Specific vs "Non-Specific" Pain

SUMMARY:

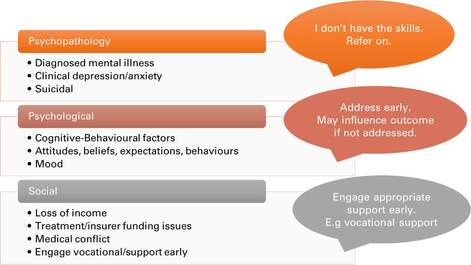

How Do You Manage Psychosocial Factors in the Clinical Setting?

SUMMARY: How do you interpret the results of randomised controlled trials when they include such a wide spectrum of patients?

SUMMARY:

Do you use manual therapy in the treatment of shoulder and low back pain?

SUMMARY:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDr Angela Cadogan, PhD. NZ Registered Physiotherapy Specialist (Musculoskeletal) specialising in the diagnosis and management of shoulder conditions. Clinical insights on shoulder research. Critical thinking. Clinical reasoning. Multidisciplinary collaboration. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed